This year has already seen significant progress in the government’s commitment to establish a body – a “Voice” – that would allow Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to have a say when the government and parliament make decisions and laws that affect them.

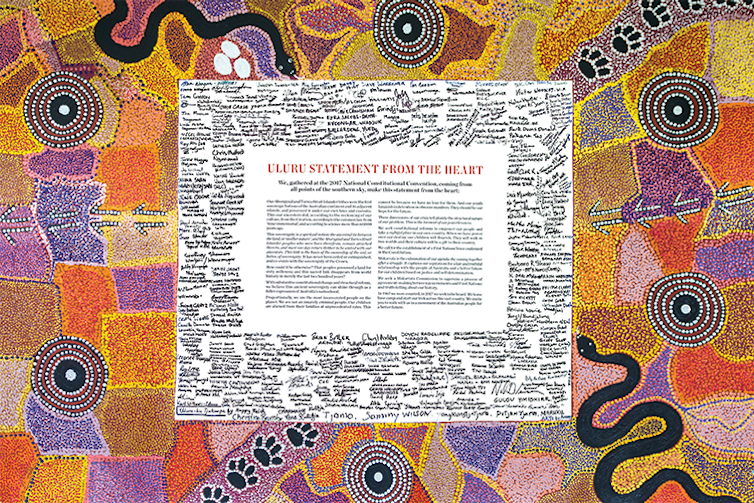

In pursuing that Voice, it has released the Interim Report to the Australian Government on Indigenous Voice Co-Design Process. This latest report is anchored in the historic Uluru Statement from the Heart, which called for “the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution”.

However, concerns have emerged from those involved in the co-design process and public law experts that the Uluru Statement’s call for constitutional enshrinement – or protection – of the Voice, is going unheeded.

Read more: 'A worthwhile project': why two chief justices support the Voice to parliament, and why that matters

What does constitutional enshrinement mean?

To say the Voice is “constitutionally enshrined” does not mean all of the detail of its design is put into the Constitution. It also does not mean it can only be changed with a referendum.

Rather, it means the core function of the Voice should be included in the Constitution, alongside a power enabling the Commonwealth parliament to determine its composition, powers and procedures in legislation.

As former Chief Justice of Australia Murray Gleeson explained, the Voice would be “constitutionally entrenched but legislatively controlled”.

This establishes a balance between a constitutional protection of the Voice while allowing it to be adapted to future circumstances.

The latest report is anchored in the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Image: ulurustatement.org

Why hasn’t the government committed to it yet?

In 2018, a parliamentary committee considering proposals for constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people concluded that a Voice was the only serious reform proposal on the table. This is unsurprising.

An increasing majority of Australians want to change the Constitution to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The government has committed to holding a referendum to do just this.

Successive processes have emphasised how important it is that the form of recognition accord with the wishes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Through the process that led to the Uluru Statement, a constitutionally enshrined Voice is the only reform that has garnered the collective endorsement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Read more: Ken Wyatt's proposed 'voice to government' marks another failure to hear Indigenous voices

However, the parliamentary committee recommended more detail be added to the concept of the Voice before a decision was made as to whether it be constitutionally protected or established only through legislation.

This “two-stage” approach is the genesis of the government’s current process. The government has appointed three groups to assist it to develop the detail of what a Voice would look like and how it could work. The interim report is almost 400 pages. Public submissions are open until the end of March. The working groups have undertaken significant work in the lead up to this consultation. Some matters of design appear relatively settled in the report; others have been narrowed down to a couple of options for feedback.

The terms of reference for the national Voice specifically excluded making recommendations about constitutional recognition. This accords with the committee’s advice to do more work on the design first, before deciding about whether to constitutionally protect the Voice.

Nonetheless, they have invited comment on this issue by stating their model fulfils the function of being a Voice to both the parliament and government.

The Voice will need constitutional enshrinement to properly perform its role. Photo: AAP/Mick Tsikas

Why the government must commit to constitutional enshrinement

The government’s attempt to defer deciding whether the Voice will be constitutionally protected has received a large amount of push-back. For instance, late last year, it was reported the national working group was divided on whether it could finalise its work without making a recommendation about constitutional protection.

In a submission to the co-design process, more than 40 public law experts from across Australia have argued that if the government is serious about establishing a Voice with the objective of providing the views of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to the government and parliament, it must commit to it being protected in the Constitution. Without constitutional enshrinement, the Voice will not have legitimacy. It will not be able to achieve its objectives and perform its functions.

The interim report gives the Voice the right and responsibility on behalf of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians to advise parliament and the government on matters of national significance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Its success in doing this will turn on the legitimacy and authority of the Voice, and how seriously its role is taken by parliament and the government.

Constitutional enshrinement will require a referendum, which will educate Australians on the role of the Voice, and provide their endorsement of it. A Voice simply established by legislation, without this public support, runs the real risk of being ignored or abolished by parliament. Constitutional enshrinement also confers constitutional status on the Voice, which signals that it is a foundational institution, establishing its legitimacy into the future.

To perform its role, the Voice will also need constitutional protection to give it stability and certainty, while still allowing for flexibility in its design into the future. Constitutional protection is needed to prevent the parliament from abolishing the Voice. It also prevents chilling of its performance because it faces the on-going possibility of abolition.

Constitutional enshrinement is vital for the Voice’s effectiveness. The possibility that a decision on constitutional enshrinement might be put off until after the Voice is designed, or even until after it is initially established by legislation, risks enshrinement from occurring in the future.

Indeed, legislating first would dissipate the current popular momentum for constitutional enshrinement of the Voice, and likely set it up to fail.

Gabrielle Appleby, Professor, UNSW Law School, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.